The PROBLEM SO FAR – or – why you need to think everything

through – or – how a seemingly simple change has cascading effects.

The back story:

whammy bars. In the 1950’s, Leo Fender and Co. in a fit of inspiration/madness

started adding ‘tremolo bar/tailpieces’ to their Stratocaster model electric

guitar as standard issue. There is generally some confusion about the

difference between ‘tremolo’ and ‘vibrato’, not least because the two words

have often been used interchangeably, and sometimes a tremolo tailpiece has

been referred to by the manufacturer as a vibrato tailpiece, but the effect has

been used throughout rock & roll music almost since its inception. The

effect, by hitting/depressing the tremolo (whammy) bar produces a wavering

sound much like vibrato in a singer’s voice. It is an ’emphasis’ effect (just

as a piano has ’emphasis’ pedals). Technically, though, vibrato differs from

tremolo (in guitar playing lexicon) as the former is more like hitting an

on/off switch, where the pitch remains constant but with distinct separation

between volume peaks – more of an ah-ah-ah-ah-ah sound, whereas the latter

achieves its wavering effect by variation in pitch – think of the sound running

up and down a roller coaster track. The tremolo/whammy bar achieves this effect

by de-tensioning/re-tensioning the guitar strings at the bridge. As the whammy

bar is attached directly to the bridge, by pressing down on the bar, the bridge

pivots forward on a fulcrum point, slackening the strings and thus lowering the

pitch, and releasing the whammy bar (or pulling up on it) allows the powerful

springs that attach the unit to the guitar body to snap the strings back to

full tension and thus back to true pitch – in theory.

Vibrato can be achieved by the fretting hand of the guitar

player by a kind of ‘waggling’ motion of the finger pressing on the string as

it is ‘fretted’, or, more commonly for electric guitar players, through a

vibrato effect built into the guitar amplifier – an effect that Fender supplied

(and still does) on many of its amps. Perhaps the clearest example of the use

of this vibrato/amp effect is to listen to almost any song played by Pops

Staples of the Staples Singers. It’s just Pops on electric guitar (a Stratocaster

into, probably, a Fender Princeton Reverb amp – or perhaps a Twin-Reverb amp)

and his singing family.

Tremolo can also

be achieved by the fretting hand of the guitar player by moving the depressed

string ‘across’ the fret board while playing, as this adds tension then

releases tension on the given string and thereby causes a change in pitch – or

– also on the electric guitar so equipped, by hitting the whammy bar. Clear

examples of use of the whammy bar are to be found all the way back in the 60’s

by almost everything from The Ventures, the Shadows on ‘Apache’ (they even did

a very credible version of Santo and Johnny’s ‘Sleepwalk’, originally done with

a (pedal) steel guitar, by judicious use of the tremolo bar), and even through

our current time by that wild man of the whammy bar, Jeff Beck. Some of my

all-time favorite whammy bar work (with added echo and reverb) is on Chris

Isaak’s version of ‘Wicked Game’. Obviously, the whammy bar has been important

to rock guitar sound over the decades, but I’ve resisted putting them on my

electric guitars. Why? Because, in general, they’re unreliable pieces of crap!

More in Part 2.

Part 2: The

PROBLEM SO FAR – or – cascading negative effects unleashed.

All right. So,

whammy bars – love them and hate them.

Tremolo/whammy

bars work by slackening/de-tuning and then re-tensioning/re-tuning the guitar

strings to create that wavering sound effect. In theory, everything should work

just fine, but they don’t, primarily for one of two reasons that I call either

weak bridge/strong springs or strong bridge/weak springs.

For whatever

reason, Fender never really put that much effort into fine-tuning its tremolo

bar/bridge set up. They have the weak bridge/strong springs get up. They

provide a fulcrum point for the whammy bar by anchoring the top/front edge of

their bridge to the guitar with two somewhat loosened screws and allow for the

strong springs on the underside of the guitar (recessed into a cavity) to keep

the bridge pulled down tight to the body of the guitar. The more aggressively

the whammy bar is used, the looser the screws holding the bridge in position

become and the less the springs can be relied on to return the strings to

pitch. On top of that, no one took into account that as the string tension is

loosened through whammy use, the tautness of the strings at the tuning peg end

of the guitar (at the headstock end) slips and when tension returns, the string

tends to return to an out of pitch spot. Upshot: for anything other than mild

whammy bar deployment, you’re constantly retuning the guitar. As often as not,

one or more strings is out of pitch to the other strings most of the time. Not

necessarily by much, but enough to be annoying to people like me. Jeff Beck

doesn’t care because he doesn’t really care about ‘being in tune’ to begin

with.

Gibson, as the

other major historical manufacturer of electric guitars didn’t deal effectively

with the tremolo bar issue either. They made a tinny, piece of crap one based

on Fender’s set-up that they deployed on some of their electrics, but on their

flagship guitar, the Les Paul model, they pretty much avoided the whole issue

by not offering one. If one was added, it was usually the granddaddy of

aftermarket whammy bars, the Bigsby Vibrato (there’s that vibrato/tremolo

confusion again) – developed sometime in the 1950’s I think. The Bigsby Vibrato

is what I would call the strong bridge/weak springs version of the whammy bar.

They had a very solid and sturdy connection of the bridge to the guitar body,

but they relied on a self-returning spring mechanism (much like you’d find in

self-closing hinges mounted to swinging doors like you’d see in a restaurant

coming out of the kitchen) that was not really strong enough, in my estimation,

to reliably do the task at hand. Changing string gauges could mess things up,

and you still had the same problem at the tuning peg end of the guitar of

losing string tautness. So neither system really worked without spending a lot

of time as a player re-tuning.

Things changed,

however, when in the 80’s there was a great flurry of innovation from

after-market manufacturers. People like Floyd Rose developed a ‘locking

tremolo’ that dealt with the de-tensioning/re-tensioning issue at both ends of

the guitar. With a better bridge movement mechanism and (key) a locking nut

that clamped the strings into immobility at the headstock end to eliminate the

string slippage that happened before. With the uncontrollable slackness issue

dealt with by keeping each string limited to a very specific length and locked

down tight, the player could dive bomb with his whammy bar to his/her heart’s

content, and the strings would snap back to perfect pitch every time – in theory.

Players like Eddie Van Halen used the locking tremolo to great effect and he

became famous for his whammy bar ‘dive bombing’ effect where he would

de-tension his strings so completely they would lose all sound, then he would

pull the bar up and they sprang back to life. While the Floyd Rose tremolo, and

others like it were a definite improvement, they were difficult to adjust once

set. The process was so arduous, that unless things were severely out of tune,

you didn’t really want to mess with it. So – ultimately not the answer either,

which takes me to Part 3.

Part 3: The

PROBLEM SO FAR

Ok, so I haven’t

quite gotten to the problem yet, but I wanted to explain why I’ve avoided

putting tremolo/whammy bars on my electric guitars – you spend too much time re-tuning

the guitar instead of playing it. Problem is I really like what they do.

Several months ago I ran across a new

manufacturer of whammy bars/bridges call Trem-King, that promised that they had

solved much of the inherent problems with the standard tremolo mechanism (as

outlined in parts 1 & 2), I checked out their product, decided that I

should give it a try and see how well it works. No problem.

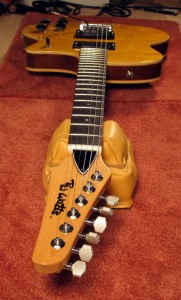

I’ve spent several years fine-tuning guitar

designs where I’ve largely worked out all the kinks for my desires, and I

thought I’d just adapt one these to allow for a tremolo bar addition – which is

what you see in the picture. I knew I would need to do some modification, so

after getting the new mechanism, I measured carefully and realized I’d have to

make the body of the guitar thicker by 1/8″ to accommodate parts of the

mechanism. I did that, and after careful marking, located the position for the

cut-outs necessary for housing the unit and routed those cavities. Easy-peasy.

I had a neck that I made from mahogany (seen in the background behind the

guitar) that I wanted to use (and it had a nut adjustment I wanted to try out).

The neck is made to be of the bolt on variety (although it could just as easily

work for a glued-in – ‘set neck’ – approach). I set it into the cavity that is

routed into the body for specifically that function. Got some longer bolts that

I needed to secure the neck to the body, attached the neck, and realized that

the fret board was higher than the bridge. This is of course a no-no, as the

strings actually have to travel very shallowly ‘uphill’ to the bridge, so the

bridge can’t sit below the height of the fret board. I thought, well, I could

shim under the bridge/tremolo to raise the whole mechanism to the proper height

needed. I needed about 1/4″ of added height, and I thought it’d look kind

of clunky with that tall a shim/spacer, but maybe it’d be ok.

Then I realized

that if I raised the trem/bridge mechanism that much, the tremolo wouldn’t

actually work correctly. Ok, well the trem was really designed to work when

attached directly to the guitar top – no shim/spacer, so that meant if the

bridge couldn’t go up, the neck/fret board had to go down. I could make that

happen – just rout the neck cavity deeper to make the neck drop down further in

the body. Then I realized that the ‘heel’ of the mahogany neck I had planned to

use (you see it sticking up vertically about 3/4 of the way down the neck)

would now stick out below the bottom of the guitar when in place. Yes, I could

trim down the heel, but I thought that’s kind of butchering the neck, so I

decided to use another neck (maple – that’s on the guitar) that’s of the more

traditional bolt-on variety. It’s recessed as far as I can go into the guitar

body, and now I had to go back to the shorter bolts to attach the neck. I might

just have gained enough room for the strings to clear effectively, though I may

have to still increase the overall height at the bridge a little. Now, though,

the pick-ups, which work fine in my normal set-up, stand up a little too tall

compared to where the strings will cross over them, so I will have to drop

those down into the body further in order to make them work, but if I do that

on the rear pick-up, I will be into the spring cavity that controls the tremolo

on the underneath side of the guitar. So now I have to consider whether to go

with a whole new set of pickups that attach differently in order to make things

work. It would have been easier, perhaps, to start from scratch with a whole

new design rather than trying to adapt one I had already “worked

out”. And one little ‘not completely thought through’ modification has

caused a cascading series of “fixes” that may yet prove to be

unworkable. We’ll see. It seems you can never spend too much time thoroughly thinking the seemingly simple things through.